Ben Horowitz’s The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers offers advice on sticky business situations. His past experience, good and bad, is served up for your benefit. The writing is crisp, direct and eschews simple answers. When you inevitably find yourself in complex, difficult to manage situations, this is the book you’ll reference. It’s an effective mix of been-there-done-that wisdom and practical, put-it-to-use-right-now takeaways.

The following are the quotes I found especially helpful in a managerial role and with an inclination towards organizational design and process. Your mileage may vary, of course. Page numbers are from the hardcover 2014 edition.

- It’s a good idea to ask, “What am I not doing?” (pg 52): I think this is meant to be in the vein of “what’s slipping through the cracks that I shouldn’t let slip?” And that’s great advice. You can also read it as “I shouldn’t do everything myself.” Delegating is important although it can come at the cost of being perceived as lazy or lacking a proactive, can do attitude.

- What’s the secret to being a successful CEO? There’s no secret, but one skill stands out- ability to focus and make the best move when there are no good moves (pg 59): As a researcher, I always want more data. And beyond that, I want to postpone decisions as long as possible to allow new data to materialize. But at some point, you have to make a decision based on what you know.

- Don’t be too positive. Tell the truth. Give problems to those who can solve them and are motivated to do so. Transparency engenders trust,

gets more brains to work on hard problems, and encourages problems to be surfaced rather than hidden (pg 65): Of course, don’t be too negative either. It cuts both ways. I’m the glass half full guy at lot of the time and it’s taxing on coworkers, bosses, clients, wives, etc. Hence all the bad jokes. : ) - Layoffs (pg 71): Focus on the future, not the past

- Don’t delay- once the decision is made, do it ASAP

- Be clear that the company’s performance failed, not individuals. Some excellent people will be lost in order for the company to continue

- Train managers- they need to explain what happened, explain that the employee is impacted and the decision is non-negotiable, and they should know and present all the benefits and support the company plans to provide

- The CEO needs to address the entire company which will give some air cover for a manager to do the individual firing. The message the CEO gives is for the people who are staying, not those that are going.

- Be present and visible after the firing. Show you care by being available.

- I’ve been around layoffs, been laid off, but haven’t actually let people go, but from the experiences I’ve had around this topic, this is great. Especially the fifth item saying the CEO’s message is for those who are still around, not for those leaving.

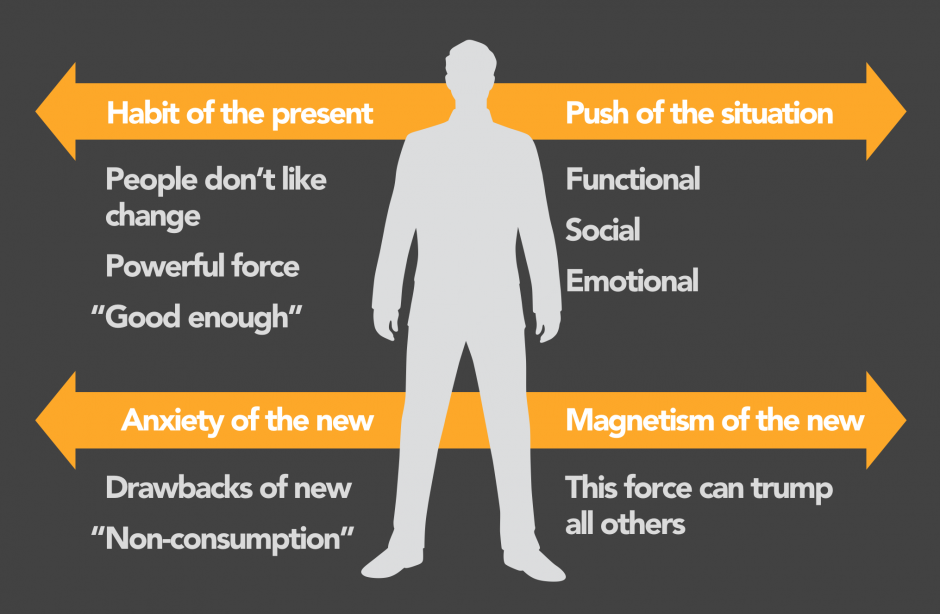

- There are typically no silver bullets, only lead bullets. Sometimes, you have to admit your product is inferior. Improving it is the first and only thing to do. Everything else is tangential (pg 88): So many projects fall into this category that it’s surprising anyone needs to mention it. It doesn’t take long to realize a product is crippled in some way. Usually it’s because the business model will only succeed if it can change people’s existing behavior rather than leveraging it.

- No one cares about your problems. Just do your job (pg 91): Oh, it’s easy to complain (and I do). Instead, do something about it. If that fails, try again. If that fails too, ask whether it’s you/your ideas or your organization/situation. It might be the latter in which case it may be time to go.

- Train your people. Why? (pg 106)

- It increases productivity

- It creates a way to manage performance by setting expectations

- It keeps product quality high

- It helps retain employees through good manager/employee relationships and keeping employees learning and challenged

- Of course, don’t just train for training’s sake. Have a plan. Why this conference for that person? Why this topic now? Why group trainings rather than one offs? Etc.

- Management debt, like technical debt, makes things easier in the short run, but kills you in the long run. Don’t fall prey. Common management debt scenarios (pg 134)

- Keeping two good people who compliment each other when one person should suffice.

- It creates reporting issues, direction and decision confusion, the two people may begin to work cross purposes, etc.

- Overcompensating an employee only sets you up for skewed salary ranges and the wrong incentive structure.

- Not formalizing feedback will slowly chip away at clarity and focus for employees.

- My favorite these days is not defining who has what role on a team. You’re bound for confusion and misdirection down the road.

- Bill Campbell’s methodology for measuring executives (pg 174)

- Results against objectives

- Management: are they building a strong & loyal team?

- Innovation: short term is easy, but imperils long term effectiveness

- Working with peers: effective at communicating, supporting & getting what they need from other execs

- Above my pay grade, but worthy to know now.

- Culture does not make a company because it takes two things to make a company and they matter more than culture (pg 179)

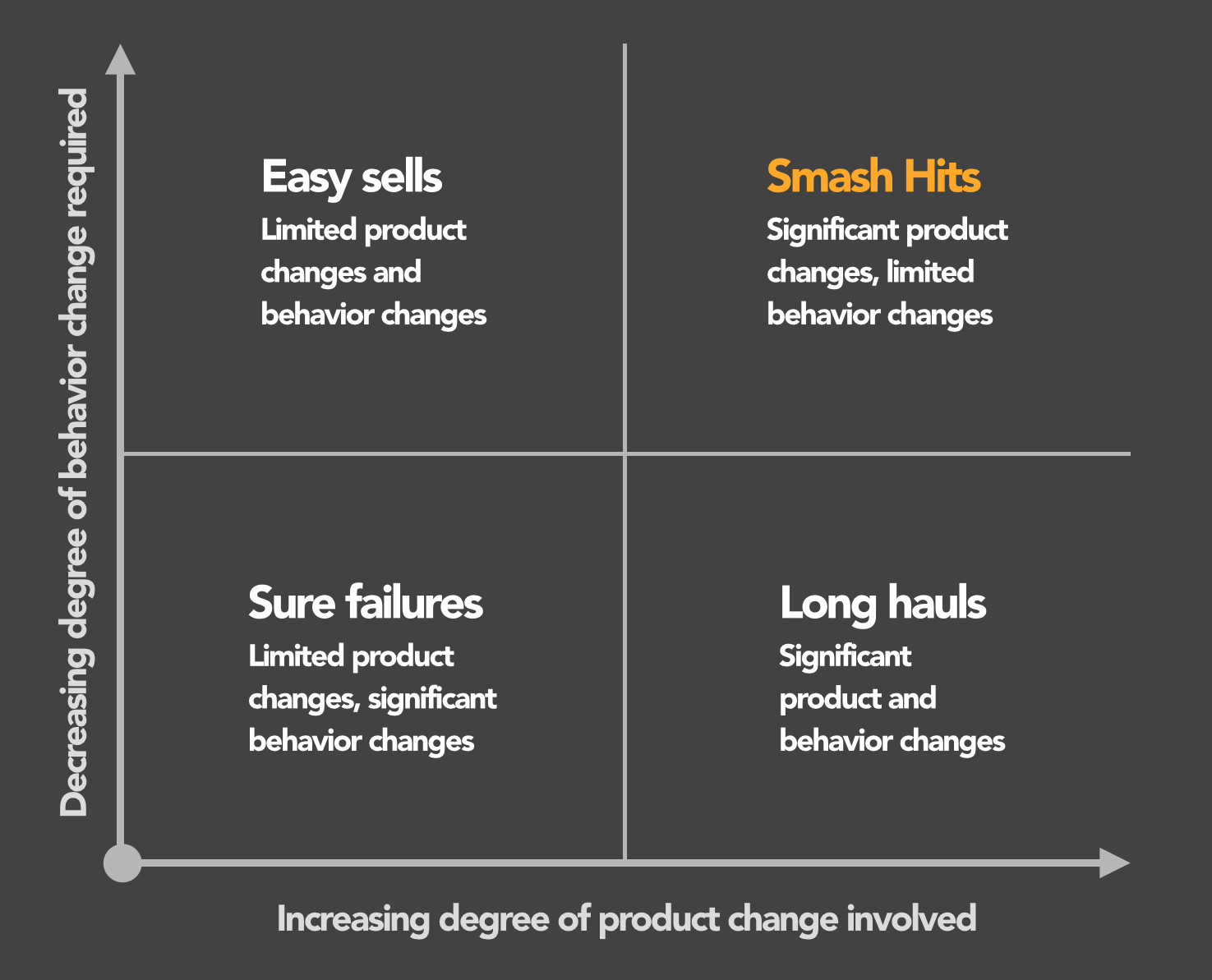

- Build a product that’s 10x better than the competition. 2–3x isn’t enough to get people to switch

- Take the market: competitors won’t sit by and watch you take market share. You need to get it and hold it ASAP.

- Culture is important after the above two things are accomplished though.

- Part of this goes back to the quote above regarding that sometimes your product just stinks and needs to be fixed from the ground up. No one gets excited over a little better. Too much inertia from the status quo keeps those people from budging.

- Focus on a small number of cultural design points and they will influence behavior over the long term(pg 181): A mission statement makes my eyes roll too, but the exercise of making one elucidates what’s most important. Then again, there are a lot of bad mission statements out there.

- Three things become difficult as you grow (pg 186)

- Communication

- Common knowledge

- Decision making

- The idea is to grow but degrade as slowly as possible along these dimensions. Three things can help a company cope:

- Specialization of skills among staff: if you find that getting some one up to speed along all dimensions needed takes longer than just doing the work yourself, you need to invest in specialized talent.

- Organizational design: all org designs are bad. You need to choose the least of all evils.

- Process: create process as needed as the company scales. process = communication

- Choose an org design that best facilitates communication internally as well as externally with customers. Steps for org design (pg 188)

- Figure out what needs to be communicated: list the most important knowledge and who needs it

- Figure out what needs to be decided: what types of decisions need to be made most frequently and how can they be maximally grouped under a single person?

- Prioritize the most important communication and decision paths: for example, is it more important for product managers to understand product architecture or the market?

- Optimize for today’s needs- you can reorg in the future, if needed

- Decide who’s going to run each group: make this decision subservient to the communication and decision needs of employees

- Identify the paths that you did not optimize: don’t ignore these entirely

- Build a plan for mitigating the issues identified in the previous step: patch the problems you’re knowingly taking on in the last step

- Process = communication (pg 190)

- Helpful things to keep in mind as you build processes:

- Focus on the output first: what should the process produce?

- Figure out how you’ll know if you are getting what you want at each step in the process

- Engineer accountability into the system: which person and which group is responsible for each step? How can you increase the visibility of their performance?

- Don’t add process too quickly or else the company will seem heavy and slow. Anticipate growth and design process for it proactively, but don’t over anticipate growth.

- Three long quotes, but delicious in combination. There’s a lot to unpack here, but it’s worth the effort. What is typically very vague and at arms length will, after you put in the work, have rationale and solidity.

- Ones [a type of employee that Horowitz defines] are strategic decision makers. Twos [another employee type] are execution focused. Some people are ones in their functional role and twos at the executive level. Ones who have other ones reporting to them can be counterproductive since each wants to set their own direction (pg 214)

- Leadership has three traits (pg 219)

- An ability to articulate a vision: is it interesting, dynamic & compelling? Compelling enough for employees to stay even when it doesn’t make sense?

- The right kind of ambition

- The ability to achieve that vision

- I assume ones and twos can both be leaders, just in different capacities. I wonder if ones find it easier to be visionary though.