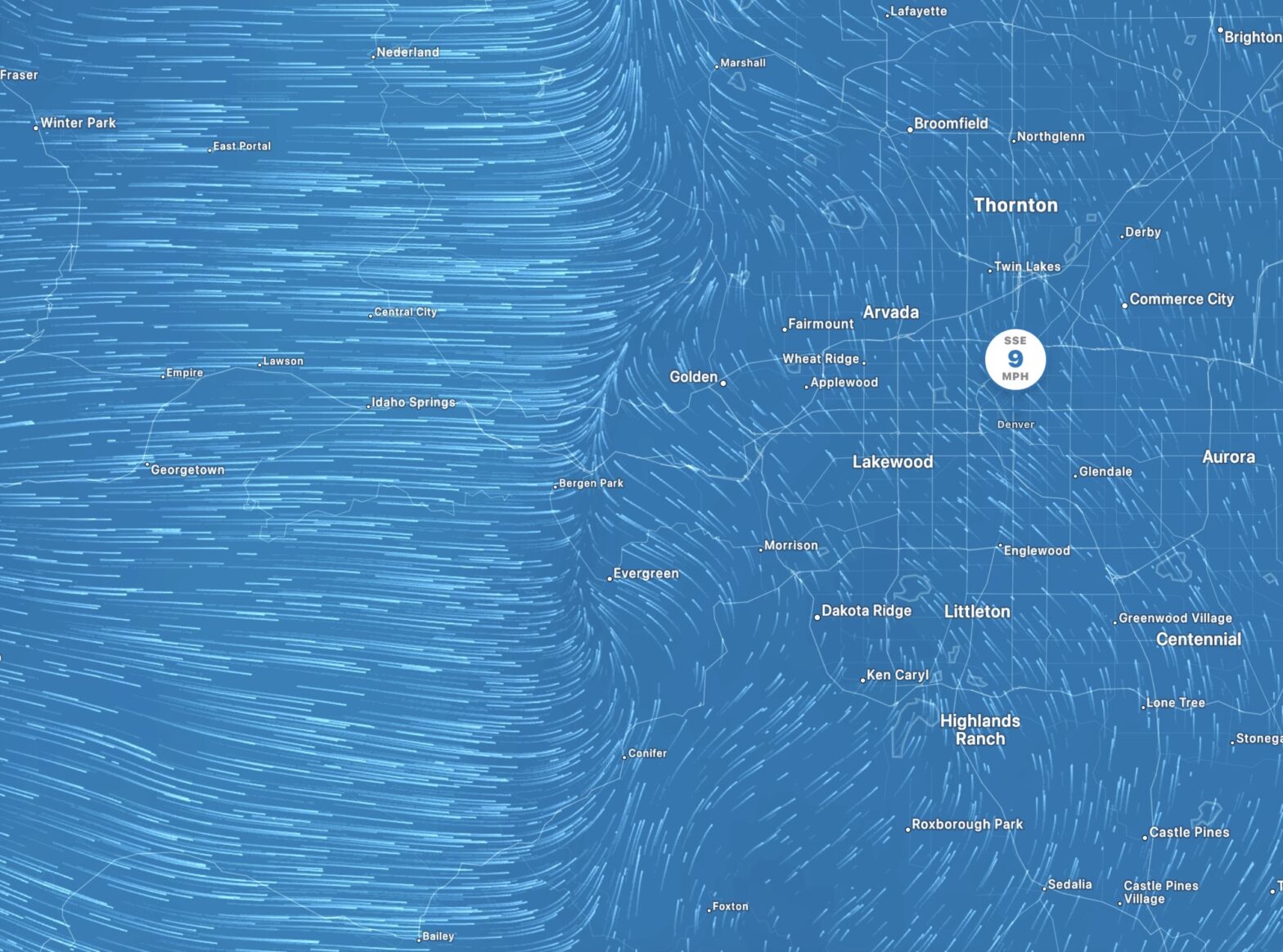

Here’s the wind pattern in the Denver, CO area. For those who don’t know, Denver sits adjacent to the Rocky Mountains making the city’s topography flat in comparison. Given that, you’ll no doubt make the connection between the wind pattern and landscape features. It’s fascinating to see how the wind screams down the mountains and effectively dies. A wall of wind.

Italian Doors

Here are all the doors I snapped during our trip to Rome, Florence, Montepulciano, and Montalcino in July, 2025. Yes, that’s right, I take photos of doors while on vacation.

As a bonus, here’s the hand burned door our old Sonoma County CA house sported as well as our newly painted door at our current Denver home.

Impressed…But Only in the Slightest, Unimportant Way

Trump is clearly a liar, corrupt, inept, incurious, narcissistic, and probably a few other negative adjectives that aren’t coming to mind. But, damn it, he has a fantastic signature.

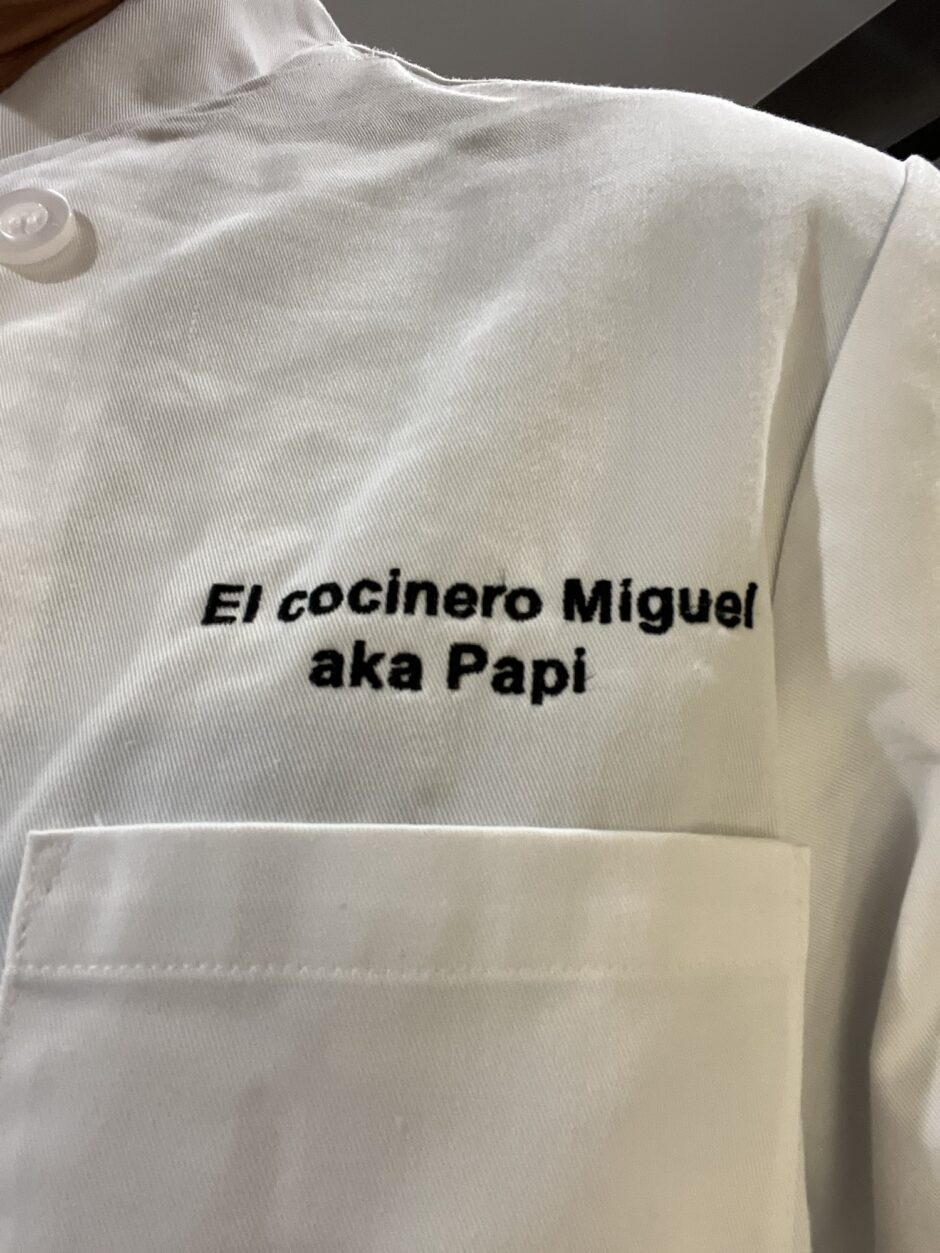

Wannabe Chef

Snowfall

We’ve had a weird first half to the 2024-2025 snow season in Denver. Cumulatively, this season’s 15.7” of snow isn’t far off the recent historical average of 18.6”. Variable differences, right? No biggie. But let’s take a closer look, shall we? Here are the average snowfall amounts, in inches, 1991-2020.

| September | .8 |

| October | 3.9 |

| November | 7.3 |

| December | 6.6 |

And here are the amounts in late 2024.

| September | 0 |

| October | 0 |

| November | 14.7 |

| December | 1 |

Anything stand out?

Another Day, Another Rush Anecdote

My go-to band, Rush, is never far from my daily existence. Spotify obviously has me pegged as a fan, Peloton rides will surprise me with a song from their catalogue (more of that please!), they pop up in movie soundtracks, and some lyrics have a knack for being spot on during particular situations. Most recently (and probably most often),Tom Sawyer’s line “…changes aren’t permanent, but change is…” captures so many of my experiences, like my new employer where changes have been enacted which are triggering follow on changes, sometimes expected and sometimes not.

The newest appearance of Rush for me was on YouTube. It’s a data visualization of live songs the band played over the course of their decades of touring. It’s limited to the top 20 songs even though their total song count tops 150. Songs written early in their career have more time to be performed, obviously. That keeps their early classics like Working Man high on the list for years on end, even decades on end. Their heyday came around the time of Moving Pictures, but that album was released nearly 20 years after they formed. For songs of that era to ultimately find themselves among the most played is a testament to their deep connection with fans (myself included, hence the lyrics noted above which come from Moving Pictures). Anyway, it was interesting to view the trend although it would have been icing on the cake to pair it with a Rush song. At nearly 11 minutes, they had a decent choice of songs long enough to use. Indeed, 2112 is nearly twice as long as needed.

Bouldering

Living in Colorado, climbing is pretty popular—even on a Friday night when I’m writing this. Maybe I should pick it back up, but that’s for another time and another post. Right now, Reese is in her happy place bouldering. And while I hate the drive to get here (there’s another bouldering place way closer), at least the playlist is great.

Heavywinter—Young Edition

This site has been around since 2004, though technically I got the domain in 2003. But I consider 2004 the true year I began to blog. I don’t write much anymore, but that’s gonna change (you’re in the presence of the proof yo!).

The Wayback Machine has snapshots of the blog even after I deleted the database back in 2009 or something??? I don’t remember exactly, but at the time I felt I had said everything I felt I needed to say or do online. I wanted a clean break from what came before to what would come next. The next thing didn’t materialize for awhile, from what I remember. I believe I wanted to have a more professional presence or something to that effect. I can see why as I read some of the old stuff. Holy crap. Talk about cringe worthy. Can’t hide from the past when it comes to the web though, even if you deliberately delete shit. Let that be a lesson to all you youngsters out there.

Ladies and Gentlemen, My Wife

All I did was switch out my jeans for sweats after I got home from work. An innocent wardrobe change. I had a brick red button down shirt and the sweats I pulled on just happened to be red too. I walk downstairs, my wife looks over, and announces “you look like a dirty pad.”

This Insta pairs well.

Random Yard Projects

South Side Fence

The house came with an old, rickety fence on the south side of the property. Our neighbors suddenly got a lot more light once it came down. Unfortunately for them, we do plan to put a new fence up though not as big. If you can actually make out a little black spot in the concrete above the downspout, good for you! That’s a post support and it marks where the new fence will go. I planned to build the fence myself, but found out with the one post support how incredibly hard it was to drill through 1950’s concrete. They don’t make it like they used to apparently. Getting the other supports in is now a job for pros. And the fence will also likely be hired out next year along with the fence on the north side of the yard. There’s simply too much work for a single person.

One thing I’d like tp point out: the house flipper laid down new concrete over the older asphalt driveway, but didn’t carry it through to this side area (you can tell by the color difference). As a result, the driveway is an inch or two higher. No big deal, right? Well, in one of the photos above, you can see a little line in the concrete next to the lumber laying on the ground. The concrete in this area is sloped toward that line, which is actually a deep cut of several inches. Before the new concrete was laid, I believe that cut continued to the edge of the driveway and provided a way for collected water in this area to drain away. Since the new concrete creates a barrier to the cut, we now end up with pools of water after a rain (or ice in the winter). Not great. I’m not confident I’ll get to this little job, but it is a job that I’ll allow myself to do with a power tool.

South Side Downspouts

When your downspouts are working this badly, it’s time to get to work. To fix it is to replace it and to replace it is to reroute it. The original downspout’s path took a severe turn in order to be positioned along a structural post. It was clogged to the point where it wasn’t doing its job anymore. I decided to reroute it straight down to avoid turns which are prone to clogs. But that meant it would have to float in space since it was going down a cantilevered wall. Who wants to see an ugly downspout out their window, amiright? The solution was to install a rain chain. We already have one at the front of the house, so this would be an exact match of it (Amazon’s 10 trillion options come in real handy when trying to match something like this). Now, clearly we need to do some planting in this area, not to mention replacing the rotting timber retaining wall. If you’ve read the post about the stone wall I built on the other side of the house, you’ll respect my lack of desire to build another at this point of my life, but I digress. You’ll notice there’s a super short French drain that exists the timber wall. In fact, there are two, one for the other downspout I replaced under the deck and against the house. Both of these will ultimately be extended out into the yard and into a dry well, but again, that work is for another day year.

South Side Patio

We have big plans for the south side patio. It’s extensive, expensive, and extends into the front area of the house. It’s a project for another year or two as we build up the courage to tackle it. Nonetheless, I did take an interim step which was to fill in the paver gaps with polymeric sand. Suddenly, what was a weed and bug infested area became quite tranquil—a nice spot to sit with a drink in your hand and good company. The bang for our buck here was pretty big and I didn’t destroy my back either. Bonus.

Tree Removal

Our yard had too many trees and shrubs. They were competing for sun and physical room resulting in asymmetrical growth and partial death. For weeks, I’d walk the yard, eyeball victims, and then go at them with saw in hand. As a result, we have fewer trees, but the ones that remain have a better chance of success. Unfortunately, the front of the house looks barren at this point having removed the majority of trees and shrubs, but there’s a plan yet to be executed to bring it back to life.

One thing I’ll linger on here are tree stumps. If you haven’t needed to remove one, consider yourself fortunate. They’re a pain in the ass. And, of course, you inevitably damage or cut sprinkler lines which you had no idea were there. This time lapse is one of the smaller (easier) root balls, but it still took hours over the course of a couple days to get out.

It’s A Wrap

I might as well pat myself on the back here and mention that I also did some DIY stuff inside the house along with the outdoor work. It’s not as sexy so I won’t go into it. And while there are some little things I’ll continue to tidy up outside, the landscape work for this year is coming to a close, much to the chagrin of my wife who wanted me to prioritize the front door area which I kept pushing back. Could I drip that work out in the remaining summer weeks? Possibly, but it’s looking like another winter will come and go before I tackle it.

From here, I’ll devote my time and effort into a job search and/or strike out on my own. It’s been a wonderful (and welcome) half year break, but an official retirement is still a ways off. I’ve enjoyed being a house husband and sometimes wonder how normal, everyday stuff gets done when everyone has a full time job. Who has time for that? But indeed, it’s time to get back into the design world and surround myself with interesting challenges and content. If you’re nearby, come over and we’ll have a coffee or glass of wine while we catch up and I give you a personal tour of all the places in the yard where I injured myself this summer.